Sold by dealer Zombolamis as a forgery by Christodoulos, but believed to be by Garyphallakis.

Originally published in the April and May 1967 issues of COINage.

Copyright © 1967 COINage (and possibly Admiral Dodson and the photographers.) Text used by permission of the publisher. Images by permission of Ken Bressett. (Some photos anonymous and perhaps by Admiral Dodson and the Athens Police Department. These used without permission. Readers encouraged to help me to discover and contact the anonymous photographers' heirs to obtain permission.) Additional Garyphallakis and Boufetis fakes not published in COINage would be appreciated for this page, if readers are aware of them.

The April 1967 article included a page of photos of the sovereign forging operation. Those photos were taken by (and perhaps copyright) the Athens Police Department in 1954. Those photos are not included here.

Dodson believed Christodoulou was dead by the time of the 1914 seizure of his dies. Tazedakis, writing in Nomismatika Chronika 1991, believes Christodoulou forged until WWII and lived until at least 1955.

Rear Admiral O.H. Dodson, U.S.N., Ret.

|

"The first fake was made

when the first collector was born." - Art Dealer Felix Landau

|

|

|

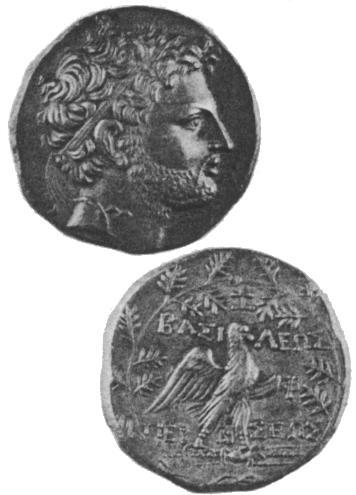

Forgery of silver tetradrachm of King Perseus

Sold by dealer Zombolamis as a forgery by Christodoulos, but believed to be by Garyphallakis. |

His lawyer was of a different breed. Young, handsome, poised, immaculate in oxford grey, he bowed courteously to my Greek interpreter, then gently inquired, "What business do you have with my client?"

This was my first meeting with John Garyphallakis, master forger of ancient Greek coins. For a month the police of Athens had endeavored to assist in located poor old John, of no fixed address. Now he suddenly appeared, surprisingly protected by a well-heeled attorney.

"It is widely reported, Mr. Garyphallakis, that you are the most skillful artist in reproducing rare and beautiful old Greek coins. Since genuine coins are so highly priced, it was my wish to meet you. Perhaps I could afford to purchase some of your exquisite copies."

Old John beamed.

His lawyer arose. "If this is all you wish, then good day, Captain." He departed graciously.

For a few minutes old John, the interpreter, and I exchanged pleasantries. John's parents were Cretan, he volunteered. Born in Crete in 1887, he was known by his cronies as "Kritikos," the man from Crete. Although given the name Nicholas, he preferred to be called John.

Sensing a sympathetic audience, old John poured fourth in the vernacular of the Pireaus water front. "I am an old man and a poor man. Hermes, son of Zeus never smiled on me. In my soul I love beautiful things. Never could my purse afford genuine coins, so I make my own. By Olympian Zeus and thrice-great Hermes I swear, never have I tried to harm or cheat. My coins are made solely for my own enjoyment."

He appeared sincere, but perhaps he had forgotten his Athenian police record of two arrests, one for robbery.

"Would it be possible," I inquired cautiously, "to acquire a few of your coins, and perhaps see how they are made?"

John pondered a moment, his keen eyes searching my mind. "My home is in the street," he replied, "my clothes are ragged. In Athens the winter is bleak. Give me each winter month two bottles of ouzo to keep the raw winds from cutting to my bones, then I'll take you to the shop in Pireaus where the coins are made." "But," he added, "we must go at midnight. By day I would be seen introducing a stranger, and I would lose my job."

Since neither local police nor American security personnel would guarantee my safety on a midnight visit to a forger's den, this meeting with John in the year 1956 was my closest approach to penetrating the counterfeiting gang which even today supplies fakes to some of the coin stores and antique shops of Athens.

Old John enlivened my U.S. Naval Mission office with return visits, proudly displaying for my admiration lovely ancient coins, freshly struck. Some of these coins, here illustrated, were bartered for bottle of ouzo, a Greek brandy as potent as a mixture of wood alcohol and high octane gasoline. John always pleaded with real charm the he adored his beautiful coins and never intended to fool anyone. He was the most enchanting of crooks.

One day, old John appeared with a Greek legal document, properly certified, to prove that his mischief was legal. On translation into English, this paper was a shocker!

Before describing this document, let us turn back to the year 1905 when the August issue of The Numismatist, the journal of the American Numismatic Association, carried the following warning from the German coin expert, Adolph Hess Nachfolger who resided in Frankfurt:

Beware of Christodulo!A Greek forger of this name has visited the principal towns of the continent, where he tried with more or less success to sell lots of false Greek coins with common genuine ones, especially of Northern and Central Greece. The forgeries are, for the greatest part, exceedingly well made, struck, not cast, the weights are rather exact. Principal types of the false coins are: Tetradrachms of Aenus with head of Hermes, didrachms and tetradrachms of Larissa, tetradrachms of Locri Opuntii, Amphipolis, Perseus of Macedon (one with ZOILOY beyond the head), ERYTHRAE with head of Heracles, Rv. Club and Quiver, didrachms of Argos with head of Hera. Rv. Diomedes securing the Palladium, Octodrachm of the Orrescii (Head, Historia Numorum p. 174), tetradrachm of Acanthus. Archaic octodrachm of Athens, etc.

According to the eminent Greek numismatic scholar, the late J. N. Svoronos, professor at the University of Athens and Director of the National Numismatic Museum, this skillful counterfeiter, Constantine Christodoulos, between the year 1900 and 1914, struck some 557 varieties of forgeries of ancient Greek coins and objects d'art. These coins were attractive and sometimes difficult to detect. Unlike the German counterfeiter Carl Becker who ignored the correct weight of Greek coins, the pieces of Christodoulos usually were within the weight tolerance of genuine pieces.

|

|

Forgery of silver tetradrachm of Amphipolis

Probably by Garyphallakis. |

At a later date, a nephew of Christodoulos and old John Garyphallakis, who was a friend and worker under Christodoulos, went to court to recover the impounded dies. This legal action is reported to have been based on the claim that Christodoulos was never convicted of violating Greek law. His family and friends stated he always sold his coins as reproductions.

Unfortunately, the court proceedings in the case are lost. Mr. Theodore Rakintzis, Director A, Offices in Charge of the General Security, Athens Police Department in 1956, reported that all police records and some court records prior to 1944 were destroyed when a mob burned the police building where the records were kept. This occurred during the disturbances which erupted in Athens in December, 1944.

With the records lost, we cannot be certain that the legal paper brought to my office by old John in 1956, and still in my possession, is a genuine document. But Greek legal authorities who examined the document pronounced it genuine. Certainly all known facts about the counterfeiting gang tend to support old John's claim that the court order is authentic.

A translation of the document reveals that Garyphallakis won his case in court. The opening paragraph reads in part:

On this day of January 5th of the year 1939, in Athens, I, the undersigned Constantine Constantopoulos, Director of the National Numismatic Museum, in executing orders of the Department of National Education and Cults (No. 112.097/6520 of the 28th of December 1938) and the Prosecutor's of Court of Misdemeanors, delivered to Nicholas Garyphallakis the items confiscated from him and turned over to us, according to the .. release?? dated July 12, 1937 of the policeman C. Herghispoulos (No. K.226) and the document No. 747 of the 8th Security Branch.

Among the items surrendered to Garyphallakis were: thirteen ancient coins; one hundred one (101) dies of bronze and iron for counterfeiting ancient Greek coins; two okas and 345 drachms (8 pounds, 10 ounces) of counterfeited ancient coins.

The document continues:

Upon delivery of the above articles, the receiver Nicholas Garyphallakis was advised to conform with the provisions of the law concerning the possession and transfer of the ancient Greek coins. As for the counterfeiting dies to keep them unused. We also offered to seal them, to prevent them from possible future use, in violation of the law B.X.M.S.T. articles 29-31.The document carried space for the signature of the Director of the Numismatic Museum, C. Constantopoulos, and the deliverer; of Garyphallakis as the receiver, and the name and address of the lawyer, George Tsilithras.Nicholas Garyphallakis stated and promised he would conform to the above specifications and agreed to have us take casts of each one of the above dies to insure detection against future use in violation of the law.

This document is significant to numismatists for it illuminates an event which has never been widely publicized. As a result of the Greek court decision, today, a half century after his death, the ghost of Christodoulos haunts the coin shops of Athens. The dies are still at work, producing rare coins to victimize the visitor who lacks numismatic experience and knowledge.

This tenacious counterfeit gang has shown a remarkable ability to endure beyond the loss of their skilled engraver. In fact some of the coins of Garyphallakis are considered more dangerous than those of the old master, Christodoulos.

In recent years one major outlet for the coins struck from the dies of Christodoulos has been an antique shop in downtown Athens. The shop is a small one-room store where walls are crowded with faded ikons, dingy shelves packed with objects in brass, bronze, silver, glass and clay from every part of the Near East. Candle sticks from Salonika, samovars from Sevastopol, earrings from Ioannina near the Albanian border, all fight for dusty shelf space in a confused mixture of art and junk.

A visitor to the shop is invited to use an old wicker chair at a soiled table while trays of coins are produced from a battered cabinet. The courteous elderly dealer closely watches my picking up and handling the coins. Then he readily admits that many of his pieces are imitations. (Under the Greek penal code a professional counterfeiter may be imprisoned for up to ten years, but, as in many other nations including the United States, the reproduction of antiquities is legal provided they are sold as reproductions.)

Legally protected by his admission, the dealer produces a tray of Athenian tetradrachms. Most, he says, are genuine. A few examined under class appear to be made by casting.

"Would you like to see nicer coins?" A small tin box taken from a desk drawer holds four beautiful silver coins. A tetradrachm of King Perseus of Macedonia, the head of Apollo on a rare coin of the city of Amphipolis, a stater from Lokris with the head of Persephone, and an archaic globular stater of Siphnos with the flying eagle are examined. These gems, the dealer claims, are the work of Christodoulos. When interest is shown in these pieces, the dealer declines to sell. "They cannot be replaced," he pleads, "I need them to compare with genuine coins." After gentle urging he agrees, with great show of reluctance, to part with the four coins for 1,000 drachmae or U.S. $33. My offer of 600 drachmae is met with a polite shrug. The four imitations of rare coins were finally acquired for 850 drachmae, or about U.S. $7 per "coin."

This shop carried no electric lights. Daylight filtered through a packed display window. In the dim lighting the coins were attractive. However, when later compared with genuine pieces in the collection of the Greek National Archaeological Museum and when weighed and examined by the staff of the American Numismatic Society in New York City, many tell-tale inaccuracies were evident. In spite of both the technical skill and the pride of both Christodoulos and Garyphallakis in their finished product, these tricksters never developed a genius for detail. In engraving dies, both men frequently appear to have been in a hurry.

When plans to publish and describe these forgeries was discussed with an experience and reliable Athenian coin dealer, he pleaded, "Oh please don't do that. This clever counterfeiting gang after studying your list of discrepancies will produce even more accurate and dangerous imitations." "These fellows," he continued, come shamelessly to my show to ask, 'How do you like my coins — what is wrong with them, how may they be improved?' You will just be creating more trouble for all of us if you publish."

It is then with some misgivings that the imperfections of these counterfeits are described, although the existence of these forgeries was reported ten years ago to the American Numismatic Association, the British Museum, and the American Numismatic Society.

Both of these forgers struck coins from silver obtained by melting genuine but commonly found ancient coins, such as the Athenian tetradrachms of the Third Century B.C., the issues of Alexander, and occasionally coins of Aegina. Some genuine ancient coins were cleaned to a clear, flat surface, then the forged dies of rare coins were used to produce the counterfeit. In recent years the gang is reported to have used a press to produce some of their coins.

Before turning to other counterfeiters, to collectors visiting Greece we repeat the warning — beware of Christodoulos; beware of his ghost.

A real villain of a forger, who so far has escaped the notoriety his acts deserve, was Manual Boufetis. This little-known sharper was active in Salonika from 1932 until his death about 1940. He specialized in the counterfeiting of the early and rare coins of the cities and tribes of Macedonia, and of the scarce coins of the first kings of Macedonia. Ch. J. Makaronas, Ephor of Antiquities, Archaeological Museum, Salonika in 1955, described Boufetis as "A very skillful imitator of ancient Greek coins and other antiquities." Mr. J. J. Badovgolov, a noted Greek collector and a member of the staff of the American Farm School at Salonika, reported in 1956 that among collectors in his city "all of them accepted Boufetis as an ace in counterfeiting. He was so skillful in producing replicas of original coins that sometimes even he was afraid of being cheated by his reproductions."

According to a goldsmith of Salonika who knew Boufetis, this scoundrel on trips to buy old coins from Macedonian farmers, would carry in his pockets a few of his own handicraft which he buried at a certain spot. After several months he would return to the burial area, exhorting some innocent farmers to go with him for coin hunting. Digging here and there at random they came, of course, to the treasury spot. The happy and naive farmers were told to take the pieces to coin collectors without mentioning the name of Boufetis. The poor farmers, with hand on the Bible, swore that they had found the coins digging in their own field. Collectors and even museums accepted some of these coins.

Unfortunately, further research is necessary before photographs of the forgeries of Boufetis are available. The Archaeological museum in Salonika claims to have neither coins nor dies of this man. Macedonian counterfeits studied by the writer could not be positively attributed to Boufetis.

A quarter century after Boufetis' death, his reputation lingers on. Even today knowledgeable collectors in Salonika are scared to purchase rare coins of ancient Macedonia. They still suffer from a disease they call "Boufetism."

Ancient coins are not the only pieces counterfeited in Greece. Although in very recent years the nation has made impressive economic progress, it remains by a wide margin the poorest nation in Free Europe. Most of these very poor, but warm hearted and wonderful people, well remember without their own life time at least one massive enemy invasion pouring down from the North. With invasions and resulting chaos the Greeks have seen their paper currency plunge below the value of discarded newspapers. Most can remember when ten billion paper drachmae would not but a loaf of bread. The Greek, therefore, has little faith in his paper money and is aware that it has limited value outside of Greece.

Furthermore having seen invasions crash down from the North, and realizing that the Russians may come next, every Greek craves small coins of great value, readily available, which are eagerly accepted abroad, and which he can quickly pick up and flee with if necessary. Or a coin which, if he is caught in Greece, will buy him into or out of any situation.

The only coin which meets all these exacting demands is the British gold sovereign.

No wonder a Greek daughter's dowry is counted in sovereigns. No wonder a young Greek male, when courting a girl, will confidentially ask her friends, "How many sovereigns does she have?" When negotiating a lease on our rented residence, no wonder the Greek owner demanded (but did not receive) six-months rent in advance payable in gold sovereigns.

Because the high demand and the esteem in which this coin is held, it is a popular belief that hoards of gold sovereigns lie buried in thousands of Greek backyards.

This was the situation which inspired enterprising Pantelis Sakidis, Emanuel Thalassinos, and Ioannis Kotoros to make their own gold sovereigns.

Operating in a private residence, an old house sheltered from the street by a high stone wall, these forgers used a well-equipped laboratory and machine shop to produce their gold pieces.

Several steps were involved in producing the counterfeits. A genuine English gold sovereign was placed in a metal mold and covered with moist plaster of Paris. After drying, the casts of both obverse and reverse of the coin were taken and the casts placed in a round metallic mold.

Through the upper cast a small hole was carefully bored. In this hole a small funnel was inserted. The casts were covered and the funnel surrounded by plater of Paris. When the plater dried it held together the casts with the small funnel in place. The gold, melted in a foundry, was poured into the casts through the funnel. After pouring the gold metal, the funnel was withdrawn, and the funnel hole sealed using a small iron tool. The cast was then placed in water for cooling. After cooling the forgers broke the plaster of Paris cover and the casts in order to remove the new sovereign.

The new coin badly needed face-lifting. Jagged bits of metal which protruded from the rim were removed, and the edge was crimped in a special lathe to improve the appearance of the reeding. The coin was then inspected for minor surface defects. An attempt was made to remove these defects by polishing. The coin was then ready to be placed in circulation.

As shown in the photograph, a comparison, with the reeded edge of a genuine sovereign quickly reveals this phony piece.

According to the records of the Athens Police Department, this gang, which was broken up about 1954, in spite of the crude reeding on their fakes, was successful in passing coins and avoiding detection for eight years. When the trio was arrested, a businessman-like bookkeeping record revealed a production of 11,600 gold counterfeit English sovereigns.

These forged coins are a gold teardrop in a large gold barrel. Although the London mint struck its last official sovereigns in 1917, it is estimated that in Europe and the Middle East three hundred million of these coins remain in circulation or in hiding. Among these gold pieces are most of our 11,600 counterfeit coins which could fool an eager or careless buyer.

In closing out this forgery case, the last notation in the records of the Athens Police Department reads, in translation, "The work which was being done, examined from a technical point of view, was excellent."

(A second installment on counterfeit United States coins and other forgeries encountered by the author on a 1966 'round the world trip will appear in a later issue.)

Kingdom of Macedonia

Forgery of silver tetradrachm of King Perseus 176-168 B.C.

The planchet is too small, although the weight of 16.67 gr. is within correct limits. Edge is too thick near the neck.

On obverse the beard is too heavy, beardline too sharp, eyebrows too prominent, cheek bone is raised, filet ending on neck is inaccurate.

The reverse is a better job although Greek letter "Phi" to right of eagle's wing is incorrect and plow under the eagle's feed is omitted.

Sold by dealer Zombolamis as a forgery by Christodoulos. However rim of this coin is at 90 degree angle to the field. On known forgeries of Christodoulos the rim slants. Believed to be by Garyphallakis.

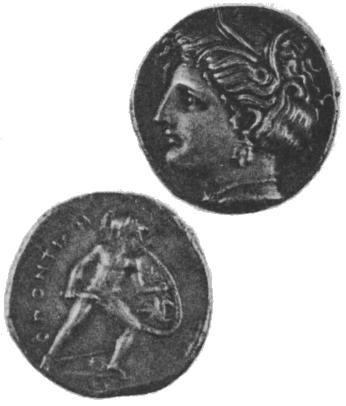

Anaktorion, a colony of Corinth, Fifth Century B.C.

Forgery of a silver stater.

At first glance the work appears to be excellent. This piece weighs 4.49 gr., which is within limits for a genuine coin. Under a glass in the fields around Athena and Pegasos many tiny pit marks have been eliminated and metal used to fill in larger holes. The coin has the appearance of a centrifugal casting. From Garyphallakis.

Locris

Forgery of silver stater, 387-338 B.C.

For the obverse the weight of 10.45 gr. is within limits. On the obverse the relief is too high, the head of Persephone tilted wrong. Edge of profile under chin and back of neck is not sharp and clear. Recesses are artificially darkened to produced aged appearance. Patina is easy to remove with a fingernail.

On the reverse the forger has Ajax leaning too far to the right. For the reverse variety of design, with spear under Ajax slanting upward, (instead of horizontal) the coin should weigh 12.09 gr.

Sold by the dealer Zombolakis as a forgery by Christodoulos. The American Numismatic Society holds a plaster cast of this die, marked "Christodoulos."

Siphnos

Forgery of a silver stater 600-550 B.C.

This is a casting, with a weight of 12.88 gr. A genuine coin in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts weighs 12.29 gr. The forgery shows several casting cracks. On the reverse the square incuse is too small. Divisions within incuse should be rough, not smooth.

Sold by the dealer Zombolakis as a forgery by Christodoulos.

Macedonia 520-510 B.C.

Forgery of a silver tetradrachm

A fine obverse with charioteer and walking horses showing less wear than most genuine pieces.

The reverse is not sharp. Easily identified as a fake. By Garyphallakis.

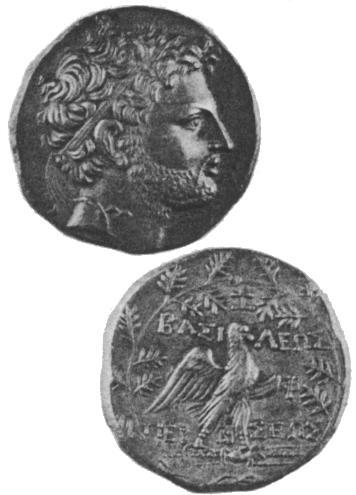

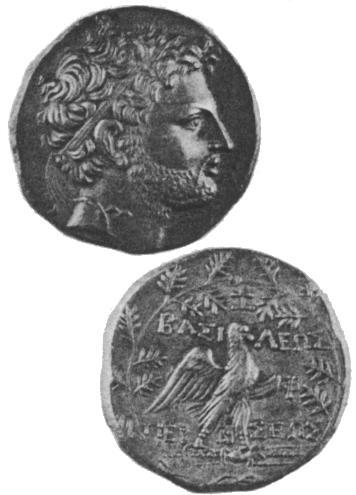

Macedonia, City of Amphipolis

Forgery of silver tetradrachm 410-390 B.C.

Excellent work but numerous minor imperfections. Weight of 14.32 gr. is correct. Artificial oxidation, possibly treated with red dust. On obverse Apollo's left eye is incomplete, nose cut and reduced.

The forger misread the coin, placing a monogram on the reverse under the race torch instead of a tripod. Some letters carelessly and hurriedly engraved.

Sold by the dealer Zombolakis as a forgery by Christodoulos, but not in Svoronos list. Probably struck by Garyphallakis.

Chalcidic League, 432-348 B.C.

Forgery of a silver tetradrachm

At 14.00 gr. this coin is too light. Average weight of genuine coins is 14.35 gr.

The obverse head of Apollo is a beautiful copy, but it was struck in too high a relief. The look in the eye is stylistically wrong.

The reverse die was more hurriedly prepared. The lyre strings are indistinct. Lyre strap ends are missing. Center of lyre design carelessly engraved.

A product of Garyphallakis.

Elis 271-191 B.C.

Forgery of a silver stater. The genuine coin weighs about 11.74 gr. This fake was tooled at the edges near the nose and back of the neck to reduce the weight, but it is still overweight at 14.29 gr. Portrait of Zeus and fine job of artificial oxidation would render this a dangerous piece if weight is not checked and rim is not closely inspected.

On reverse the eagle's wing is too high and its beak is too long and narrow.

Possibly by Garyphallakis.

|

The problem of counterfeiting is not new. The only new aspect is the appearance of these thousands of recently converted collectors, relatively well-heeled, on the one hand and, on the other hand, the poverty of desirable numismatic material. The counterfeiter has rushed in to fill this void between available, genuine, scarce coins and the demands of the vastly increased collecting fraternity. As a result, reports of new fakes crowd the pages of numismatic journals. National and international agencies are now cooperating in efforts to widely disseminate warning descriptions of counterfeits as they appear.

Edward Gans, a scholarly numismatist, has written, "The problem of counterfeiting is almost as old as coinage itself." This statement was recently confirmed. The Greek island city-state of Aegina is believed to have produced the first silver coins of the western world. These staters, with the likeness of a sea turtle, appeared early in the Sixth century B.C. Recently, American archaeologists, excavating at the Sanctuary of this Isthmian Poseidon near modern Corinth in Greece, uncovered a small but amazing hoard of these early silver "turtles" of Aegina. One coin was copper, silver plated. Were it not for a crack at the edge, this fact could not have been established, since its weight is within normal range. The technical accomplishment is surprising considering that coinage had just been introduced. There is no doubt that this coin was struck with genuine dies. Several coins of this hoard consisted of a silver shell stuffed with clay or sand. These pieces, the first-known counterfeits of the western world, are almost as early as coinage itself.

Athens also had its counterfeiters. The Athenian statesman Solon enacted a law carrying the death penalty for those caught fraudulently reproducing the coins of the city.

China, with the cunning of an old dog, is the only contemporary nation which has maintained a continuous existence for forty centuries. If we accept rings of gold, silver, and bronze and small cast bronze imitations of hoes, spades, and sickles as money, then the Chinese were using money in trade several centuries before the first western coins appeared in the bazaars of the Kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor. Terrien de LaCouperie in his book Catalogue of Chinese Coins, published in 1892, frequently mentions the acute problems of Chinese forgeries. Emperor Wu Ti (140-87 B.C.) temporarily controlled the incessant counterfeiting by rounding up the most skilled forgers for employment in his new mint. A century later counterfeiting had so infiltrated the metallic currency that "silk and hempen cloth, grain and metal in lumps are again used for currency."

Roman coins were extensively counterfeited as we know from surviving forgeries and from references in Roman literature. The writer Petronius, a master of comic satire, is believed to have been a contemporary of the Emperor Nero. Fragments of The Satyricon of Petronius, which have survived, record this passage as translated by William Arrowsmith:

'But next to literature,' he continued, 'which profession do you think has the roughest time of it? To my mind, doctors and money-changers are the worst off. Doctors, because they have to guess what's going on in the tummies of poor mankind and when the fever comes. But doctors I despise: they're always sticking me on a diet of roast duck. Money-changers come next because they have to detect the phony copper beneath the silver.' [1]

According to Henry Grunthal, Curator of European and Modern Coins at the American Numismatic Society, "The faking of coins must have been common practice in classical times as we can see by the many 'NUMMI SUBAERATI' which have come down to us. These coins are silver plated, the core of the coin being of copper, therefor the term 'Subaeratus' (of copper underneath.)"

The tradition of the forger carried into medieval times. In Germany in the thirteenth century, according to Grunthal, we find records of forgers having their hand chopped off or even condemned to death.

In a recent lecture at the American Numismatic Society in New York City, Grunthal stated, "In modern times we find the forging of coins common practice. There are even cases known where officials stooped so low as to palm off imitations made in inferior metals. The classical examples are the so-called 'Ephraimits' which where struck by a crooked Prussian mint master by the name of Ephraim. In 1753 when the Prussians occupied the Saxonian mint in Dresden, he used the Saxonian dies he found in the mint. He struck talers and their divisions, but forgot on purpose to strike them on good silver planchets. Instead he used planchets which were very rich in copper content. The people very soon became wise to this swindle and made a verse pertaining to his fraudulent coinage. A free English translation would be:

From the outside fine, from the inside limp.

On the outside Frederick, inside Ephraim.

Serious numismatists are familiar with the dismal record of famed counterfeiters over the last centuries. The imitations of Roman sestertii by Cavino and his talented assistants in Padua, the Greek classical forgeries of Carl Becker, the fakes of Cigoi, of Christodoulos, and the unidentified forger of Geneva have all been published. But this was done only after years had passed. In the interval the coins of these skillful crooks wormed their way into many notable private and museum collections.

According to Edward Gans, "The activities of these older forgers were limited in the main to coins originally struck by hand, and a really dangerous counterfeit had to be produced by an identical technique." The older electrotypes and casts could — with minute inspection — be easily detected.

But today these cunning professional crooks have refined to a high degree the methods of reproduction. Profits in machine-made reproductions of coins have soared. As an example of the problem collectors face, the German journal Numismatisches Nachrichtenblatt of March, 1961 lists over a hundred gold coins of the twentieth century from fourteen nations, all fakes and restrikes.

An even stranger twist to counterfeiting is related by Murry T. Bloom in his recently published work, Money of Their Own. He records the startling story of Jose Beraha, who set up a mint in Milan, Italy and by 1951 had cleared two million dollars through striking counterfeit British gold sovereigns. Since the coin was no longer legal tender in Great Britain, Beraha escaped conviction and lived happily in retirement.

On a recent trip abroad, the writer found in every major city visited, stark evidence of current widespread counterfeiting activity.

Shopping in Hong Kong, the worlds most fabulous free port, is a thrill. Among the concentration of clothing stores, camera, jade, gong, and ivory shops on Nathan Road and nearby side streets are numerous Chinese operated Money Change shops. A dozen if these shops were visited. All but two prominently displayed United States gold coins usually the $2 1/2 and $5 pieces. A shop owner noticed my careful observation of one gold piece, exhibited behind a glass case. He was reluctant to produce it. "We are busy now — do you wish to buy it or just look at it?" he asked. "May I examine it?" Blandly came the reply, "You can see it. If you will buy it, I'll take it out of the case."

|

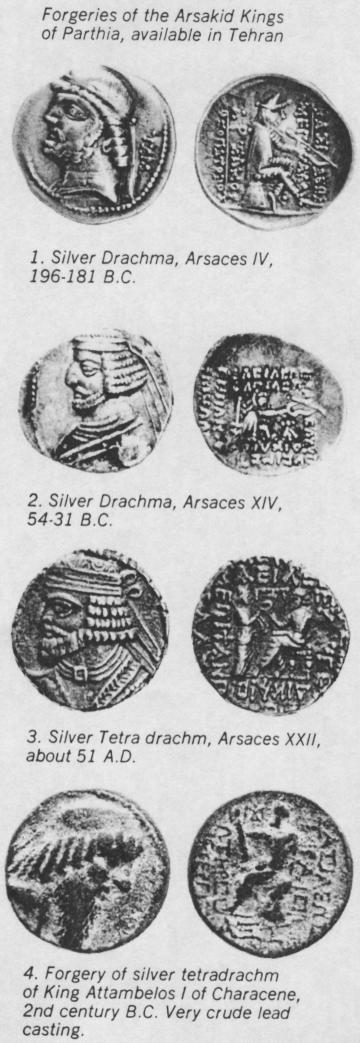

Bustling Tehran is famed for its caviar, fine rugs, delicate miniature paintings, colorful enabled flower pots, and elegant patterns on hand-printed cloth. Visiting coin collectors should not miss the breath-taking Crown Jewels of Iran beautifully displayed along with a rich exhibit of gold coins in the Central Bank of Iran.

In one shopping district of Tehran along Naderi Avenue, stores display beautiful mosaics, hand-woven embroidered silks and brocades, brass lamps, samovars, miniature paintings on ivory, sheepskin rugs and jackets, and astrakhan tribal hats. The shop owner, recommended by local Americans as the most reliable, also has a stock of coins. His small offering of about twenty silver dirhams of the Sassanian period, with the usual bust of a king and a fire altar on the reverse, appeared to be genuine. They came, he claimed, from a hoard found in southern Iran. His large assortment, proudly produced after other customers had departed, consisted of scarce coins of the Arsakid Kings of Parthia. About forty were examined; all were fakes.

Baghdad, founded twelve hundred years ago, is today a new center of industrial growth. Located on the Tigris River, which may have watered the Garden of Eden, Baghdad has preserved the rich heritage from the earliest cradles of civilization. Collectors visiting Iraq will find a fascinating display of coins on exhibit in the newly opened Iraqi Museum. Greek, Macedonian, Roman, Seleucid, Parthian, Bactrian, Sassanian — traders and kings and generals of these empires marched across "the land between two rivers" leaving behind their relics and their coins. The museum collection of Islamic coins alone numbers 50,000 pieces.

The old bazaar in Baghdad is crowded with rugs and hand-made copper products. One antique shop is loaded with articles on brass and copper and bronze which appear to have gathered dust since the rule of Haroun al-Rashid, the celebrated Caliph of The One Thousand and One Nights. Old coins were displayed in copper bowls. One bowl held about twenty unusual coins, tetradrachms of King Attambelos I, a ruler of the obscure kingdom of Characene. This nation, located at the head of the Persian Gulf, existed briefly in the Second Century B.C. Its span in history covered just sufficient time to issue a few coins. Here was an exceptional hoard of coins, seldom seen. But even a casual inspection revealed atrocious forgeries, carelessly designed, cast in lead. The dealer feigned surprise. "Many visitors buy them," he declared, "when they are all gone, I can't obtain any more." Initially priced at $10 per coin, one fake was finally obtained for $1.50.

Other bowls contained an amazing mixture of rather common Parthian silver drachms. At least ten varieties were noted. All were base metal forgeries, artificially darkened to look old, the lettering on the reverses extremely crude. The dealer, noting my dismay, tried to shift my interest to a circular, hammered copper tray showing King Nadir hunting a gazelle, guaranteed, he said, to be two hundred years old.

Located along the eastern shores of the blue Mediterranean, Lebanon, the legendary land of milk and honey, is attracting an increasing number of visitors. Driving from Beirut along wonderful beaches, or through orange and olive groves, one may visit Byblos, a neolithic city with ruins 5000 years old, view rock inscriptions of Egyptian pharaohs and Assyrian kings, walk through the majestic Roman temples at Ballbeck where Jupiter, Venus, and Bacchus once were worshipped, then return to Beirut for dinner at the Casino followed by the floor show, which rivals the best in Paris.

Lebanese are proud of the beauty of their land, its high literacy rate, explosive economic boom, and its remarkable new hotels which can accommodate 8000 visitors. Beirut, remarked one Lebanese, is the center of all activity in the Middle East, including counterfeiting.

Returning from a tour, on the outskirts of Beirut, we passed an encampment of Kurds, a tribal group who are refugees from Iraq. The colorful costumes of the Kurdish women were enhanced by elaborate necklaces of gold coins. Droplet earrings of small gold pieces further suggested the possibility of an unusual color photograph.

But no Kurdish woman would pose. All turned away claiming permission must be obtained from a man — father, husband, or brother — before they could be photographed. Not a man could be found; they were all at work or in nearby taverns drinking coffee.

In desperation, my camera was focused on a woman at a vegetable stall. She was wearing a lavish gold coin necklace and was busy selecting the least rotten from a table loaded with tomatoes, which were black with flies. She glanced up, saw my camera, and flared in anger. Picking up a handful of soft, rotten tomatoes, she advanced in savage rage, her broadside of tomatoes ready for firing. My guide grabbed my arm; we fled to the boulevard and the safety of a policeman, without the photograph.

Since this was my first unhappy experience in Lebanon, our guide in consolation suggested, "Let's go to the Gold Market in Beirut. There we may find one of the Kurdish gold necklaces. Any Lebanese girl will be willing to let you take her picture wearing it. You can tell American audiences the girl is Kurdish, no one will know the difference.

In the Beirut Gold Market, articles of gold are reputed to carry the lowest prices in the world. We could not located a Kurdish gold necklace, but United States gold coins were plentiful. Since the Gold Market trip was unscheduled, my magnifying glass was in our hotel room. The gold pieces examined appeared to be genuine. Prices were reasonable. A U.S. $20 coin dated 1897, almost uncirculated, was acquired for $40, a 1905 U.S. $10 coin for $25, and a very find Half Eagle dated 1908 for $15.

Upon my return to the Phoenicia Hotel room, the newly purchased gold pieces were examined under a magnifying glass. On the Double Eagle the hair lines on the Liberty Head were indistinct, the points of the stars slopped into the field. On the reverse the edges of stars and the rays above the eagle were not sharp. The reeding showed evidence of tooling. The entire designed of both obverse and reverse was in low relief. The $10 and $5 coins bore similar evidence of recent manufacture. It was too late in the day to attempt returning the coins.

The following morning the Gold Shop where the coins had been purchased greeted me as their first customer. This exchange took place:

Clerk: "Good morning, Sir. We hope you continue to enjoy Lebanon."

Gullible Tourist: "No, I am most unhappy. I admire old coins but these you sold me yesterday are new."

Clerk: "Why that's not possible, they are good coins!"

With a magnifying glass defects on the coins were pointed out. The clerk called in others and the store manager. All listened gravely to my comments, the conversed among themselves in an unknown tongue.

The fake coins were placed on the counter. "These are returned, place return my $80."

Manager: "We bought these coins in good faith and sold them to you in good faith. We are not numismatists, we are gold merchants. We cannot be experts in every field. Remember, we never stated the coins were genuine originals. (This was correct). Since we sold them in good faith, we cannot return you money, but will permit you to select instead the equivalent value in gold jewelry."

Gullible Tourist: "No, I just wish my money back."

Manager: "Sorry we cannot do this."

Tourist: "Then I am most unhappy. I will call the nearest policeman, and find out what my rights are."

Manager: "This is unnecessary. We wish you to be happy in our country. You bought coins for $80. You will receive a refund of $72. I can't return the full amount. After you left, your guide returned and demanded his ten percent commission. You must obtain the $8 from him."

During the next two days before our departure neither the tour company, who had furnished the guide, nor the hotel staff could locate him.

Discussing this gold coin incident with one of the leading antique and coin dealers in Beirut, I was told, "You were lucky when compared to many visitors. It only cost you $8 to learn." This dealer has an attractive stock of oriental jewelry, brocades, ivory, silver work, icons, jade carvings, and an extensive selection of coins. "Lebanon has few collectors," he stated, "because of the fear of counterfeiting." "There is a flourishing industry in counterfeiting in Turkey, Syria, Greece, Egypt, and Lebanon. The most skillful counterfeits are made in nearby nations and sent to Beirut to be sold," he insisted.

After a promise not to quote him by name, this dealer explained, "We have in Lebanon honest counterfeiters and dishonest counterfeiters." In a gold forgery the honest counterfeiter includes the correct purity of gold, the dishonest counterfeiter cheats on the gold content. "In Lebanon," he claimed, "all United States gold coins are counterfeited. The forgeries are struck, but the rim is usually reworked." He displayed trays of United States gold pieces with genuine coins and counterfeits carefully separated. His voice dropped, "You have dishonest dealers in the United States. Last year many American dealers visited my shop. Three of them made extensive purchases from my stock of counterfeit U.S. $3 gold pieces. They knew they were purchasing counterfeits."

It would require days for a visitor to absorb the history, the ruins, and the legends of Byblos. The ruins cover an historic span of seven thousand years. Recent excavations have cleared the Phoenician city and the Roman and crusader towns.

Convenient to these dramatic ruins, which go back beyond man's earliest memories, is a modern antique shop, specializing in Lebanese and other Middle East curios, handicrafts, antiques, and souvenirs. Arabic dolls, knives with gazelle horn handles, copper braziers, hubble-bubble pipes, camel bells, and curved Arabian daggers fascinate the visitor.

The store bulletin states, "Although our coin assortment goes back through the days of the independent Kingdom of Byblos more than 2300 years ago, the scarcest period is that of the Crusaders." This statement is in direct conflict with that of a leading Beirut coin dealer who said that hoards of Crusader coins, particularly silver groats, are found in large numbers. He mentioned a recently recovered hoard of the coins of Bohemund VI who ruled in Crusader Tripoli about 1270 A.D. The clay jar contained 1200 coins.

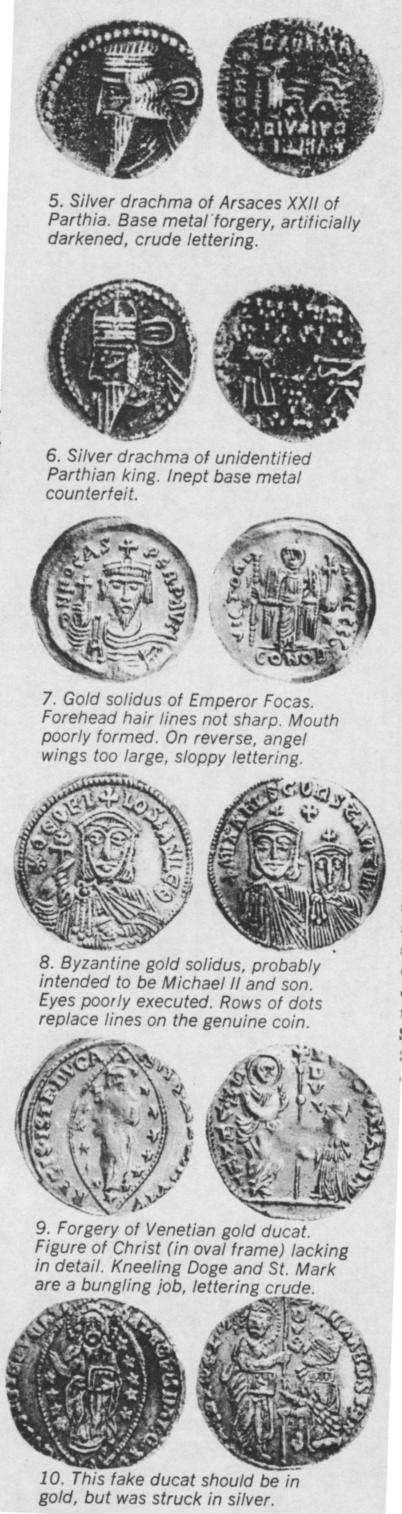

In the brief time available in the Byblos Antique Shop, only three coins were closely examined. Each piece was a gold solidus of the Byzantine Empire. One coin was excellent work, the others less accurate, but all three were forgeries. One fake, purchased for $3 and here illustrated, was so thin and the gold so malleable the coin could be folded double with the fingers.

From Beirut a round trip by car across the border of Syria and on to Damascus many be completed in one day. For six thousand years people have lived on the oasis of Damascus. The city slumbers, dreaming of the past when Damascus was the capital of vast empires. The white, flat-roofed cottages, clinging to the hillsides, remind one of the pictures from a Bible of childhood days.

The Damascus bazaar is a study in antiquity. People dress and earn their living in the saw way as the fore bearers two thousand years ago. One enterprising merchant in the bazaar claims to be "The Biggest Manufacturer of Gold and Silver Wares — Brocades Until Nine Colors — Embroideries — Leather Wares — Inlaid wood — Mosaics — Brass and Copper Wares — and Oriental Articles in Damascus."

In this shop, in a tray of Byzantine gold pieces and of Venetian gold ducats, all coins were forgeries. After the manager realized his customer recognized these coins as imitations, he sold one of each for $3.75 apiece which he claimed was the value of the gold in the coin.

Walking down "the street that is called Straight," one turns to reach another shop on Ananias Street. Here a display of Venetian ducats, which should be in gold, were all forgeries made in silver.

In Syria we were informed that the government is taking stern measures against villagers who plunder ancient ruins searching for coin hoards. Police have raided the antiques shops which serve as an outlet for these coins and seized all ancient pieces on display. As a result, the shopkeepers carefully conceal any genuine ancient coins, only displaying counterfeits which are safe from seizure.

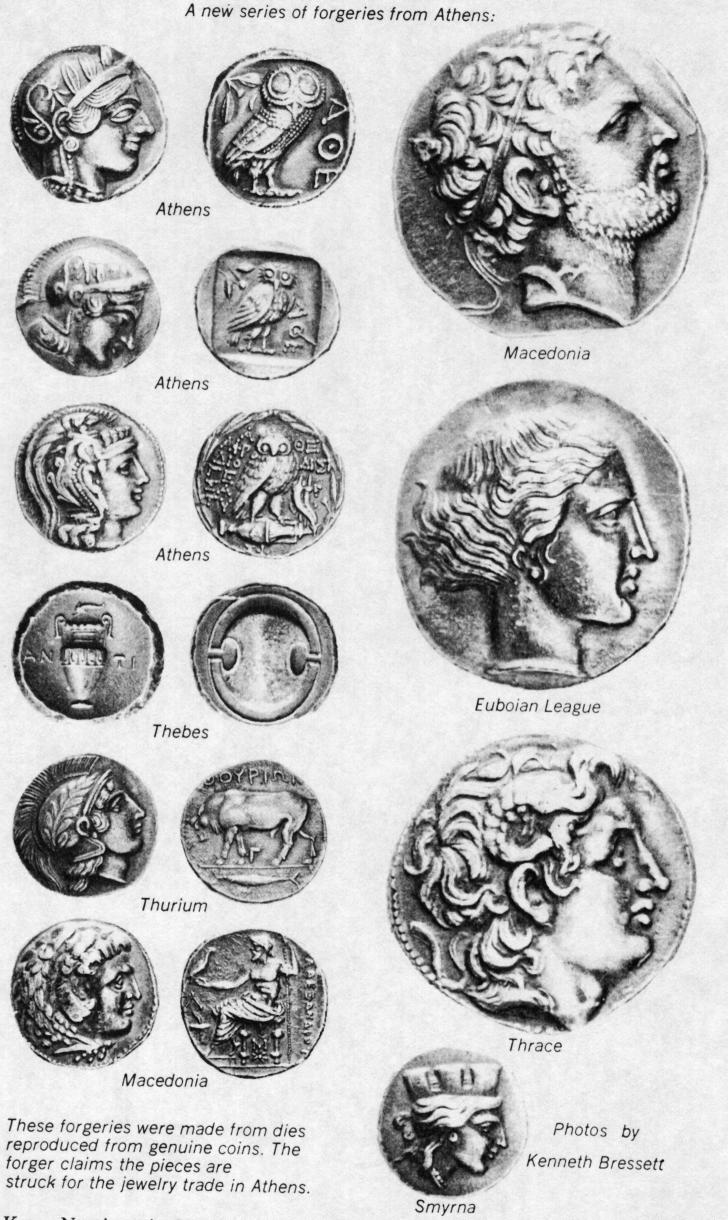

Every wester nation is indebted to ancient Greece. It was here that art and science and philosophy and medicine united to produce a Golden Age which is still revered in this thundering twentieth century.

In the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, the treasures displayed are unsurpassed. The numismatic collection ranks as one of the most impressive exhibits of classical coinage to be found in any land.

But in shopping for ancient coins, one must be alert. There is no end to the forgeries readily available. The most recent series of counterfeits to appear in Athens are struck by a Greek jewelry worker. He claims that his reproductions are made for use in cuff links, broaches, and earrings since genuine coins have become so expensive they can no longer be used in costume jewelry.

Fourteen of these forgeries are illustrated. They were ordered, were produced and delivered in two days. After bargaining, this set of replicas was purchased for 700 Drachmas or U.S. $23.30.

When new, these counterfeits have a surface sheen which is totally unlike ancient coins. The workmanship on the obverse of these pieces is usually better than on the reverse. Under microscopic examination, these fakes are vague in detail, symbols and legs of figures are indistinct, mistakes in lettering occur, and on some coins the highest surface has been scraped or flattened, and there is evidence of filing.

Today these new and clumsy counterfeits should be readily recognized for what they are. But members of the staff in the Numismatic Museum of the National Archaeological Museum are concerned. "Place these fakes in circulation for a few years," they stated, "or rub them with fine sand and they could become dangerous."

As this flow of counterfeits becomes a deluge, what can be done about it?

In every nation, laws on counterfeiting should be strengthened and enforced, but as Edward Gans has written, "Such campaigns are difficult, costly, and many require many years."

The best immediate defense against numismatic pirates is vigorous and swift publicity. When every reputable coin dealer and each national numismatic society is promptly informed of the appearance of new fakes, counterfeiting will become less profitable.

The International Criminal Police Organization and the International Association of Professional Numismatists have launched a campaign to cooperate in disseminating world-wide information on forgeries. In the United States, the newspapers, Coin World and Numismatic News, and the Numismatist and COINage magazines are effectively publicizing forgeries. To the collector these recent actions are encouraging.

The individual collector has two choices. He must buy only from reputable, experienced dealers or be willing to devote years to careful study of the coins he plans to acquire.

For the careless and the uninformed, there is no escape. In the shade of every collector stands the counterfeiter. Only judicious selection of sources of coins and knowledge of coins will protect the buyer from his shadow.

|